Balancing Difficulty

- ritaorlov

- Nov 14, 2018

- 4 min read

How do you challenge someone without making them want to bang their head against the wall? Balancing difficulty is a tricky thing, especially since ideal difficulty heavily varies depending on who the solver is.

Audience

There are puzzles out there that will challenge everyone that comes across them, but there are also puzzles that will take one player minutes to solve while another player might take hours. Player skill sets and their level and breadth of experience play a huge factor in this, so before you start trying to balance your puzzle, ask yourself who the intended audience is. Designs intended for kids, novice puzzlers, and expert puzzlers should all look at least somewhat different.

Amount of information

Amount of information is one of the key elements to puzzle difficulty. Think of a sudoku book, broken down into sections of easy, medium, and difficult. I can usually finish an easy puzzle in a couple of minutes, without any notes. A medium one might require taking down some notes but is still a straightforward solve. A difficult one might require a little extra mental gymnastics, making you think on the level of “IF x, THEN y, but IF z then…” as one might during a game of chess. Yet, a “hard” sudoku in it’s solved form is no different from an easy one - the difference lies in the amount of information presented to the solver at the starting point. It follows then, that less information means a higher level of difficulty, but take away too much information and the puzzle becomes unsolvable.

Straightforwardness

The other main factor of difficulty is straightforwardness. I find this most challenging to balance in puzzles that require making mental connections between different things. The more tenuous the connection seems, the more you run the risk of your player getting confused and frustrated. In these kinds of puzzles it’s important to leave enough breadcrumbs without completely spelling out the answer. (Often this will mean leaving larger breadcrumbs than you first anticipated.) Most importantly, you don’t want to leave your player wondering “How was I supposed to know that?”

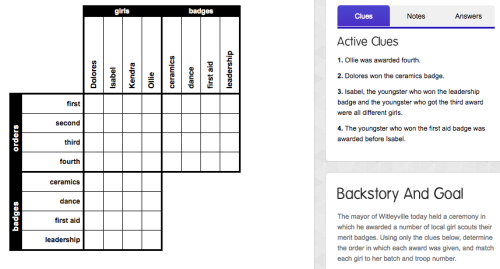

In some instances, straightforwardness is easier to manipulate, such as in this very simple logic puzzle. Here, if you took any information away, it would be impossible to solve without guessing, but what if you reworded some of the clues? For example, if you changed the first clue from “Ollie was awarded fourth,” to “Ollie was awarded after Isabel, but was not third,” it would already add one extra step to figuring out Ollie’s placement, and take the entire puzzle a tiny step up in difficulty. Similarly, adding layers to a puzzle will also increase the difficulty, as multiple steps require thinking on several different levels simultaneously.

Image credit to https://www.logic-puzzles.org/

Outside knowledge

Puzzles shouldn’t require outside knowledge to solve, but if having it makes it easier, that’s not necessarily a problem. For example, someone with poor spatial reasoning skills will have a harder time solving a three-dimensional puzzle than an architect might, but ultimately may figure it out with some devoted effort. If you present a non-musician with a bunch of sheet music to decipher though, you can expect a different result. To that end, make sure you include enough information so that the puzzle can be solved without special knowledge (unless of course that knowledge is what you’re testing).

Too easy, too difficult

Easy puzzles are not necessarily bad - there is a time and place for everything. Easier puzzles make for a great introduction to a concept that might increase in difficulty, similarly to how video games might include a tutorial, (or better yet, some sort of organic onboarding). You might breeze through the first few levels of a game, but they are there to teach you some basic concepts before presenting you with a challenge that otherwise you may not have the resources to solve.

When playtesting, take note of where people get stuck. As a general rule, if every playtester gets stuck on a puzzle, it usually means that it would benefit from an extra clue to guide the player in the right direction. If everyone is able to solve it, it’s possible that it is just easy, but it also might be a puzzle of moderate difficulty that is just very logical to whoever comes across it. Depending on what level of challenge you’re looking to create, you might leave puzzles at anywhere from a 25%-100% solve rate (without needing an extra clue). The major thing to be aware of though, is the reason why the other percentage of people is not solving it - is it because they are missing something, or is it because something about your design is too confusing or obtuse?

“Impossible” puzzles

Some people make puzzles so difficult that while they may technically be solvable, they’re not really designed to be solved. You may have heard of things like Cicada 3301, created by who-knows-what-sinister-agency-or-organization, that only a tiny handful of people may have ever completed, but I’m talking more about things like an escape room with a 3% win rate. Real talk: your 3% win rate puzzle is probably not very fun for 90% of people. I’m not a believer in 100% win rates, but I urge creators to consider why they’re designing in the first place - to snicker as they watch people struggle, or for people to enjoy their game as much as possible?

What do you think? How do you balance difficulty in your puzzles?

![What Are We Playing? [Jan 2026]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/d9bb7d_1868e069f3b846f3b5f0dd1901313309~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_980,h_551,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/d9bb7d_1868e069f3b846f3b5f0dd1901313309~mv2.png)

![What Are We Playing? [Nov 2025]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/d9bb7d_223377e9b6c840148df7e9c31ff38804~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_980,h_551,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/d9bb7d_223377e9b6c840148df7e9c31ff38804~mv2.png)

Comments